Figure

11 [31] shows a specimen of provisional paper for 1840 - 1841 which

was prepared by applying a handstamp to unwatermarked “common paper”.

The “rubrica” beneath the stamp prove that it is provisional paper.

This provisional issue was revalidated for use for the biennial period

1851 - 1852. The design of the stamp differs from the

design of the stamp of the regular

issue of 1844-44. The design of the stamp of the regular issue

is shown in Figure 10. The sheet shown in Figure 13 was not used

and at the end of the biennial period of 1844-45, a hole about 1.5 cm,

in diameter was punched through the center of the stamp in order to invalidate

the stamp in accordance with the provision of Article 64 of the Royal

Cedula of February 12, 1830. [32]

Figure

11 [31] shows a specimen of provisional paper for 1840 - 1841 which

was prepared by applying a handstamp to unwatermarked “common paper”.

The “rubrica” beneath the stamp prove that it is provisional paper.

This provisional issue was revalidated for use for the biennial period

1851 - 1852. The design of the stamp differs from the

design of the stamp of the regular

issue of 1844-44. The design of the stamp of the regular issue

is shown in Figure 10. The sheet shown in Figure 13 was not used

and at the end of the biennial period of 1844-45, a hole about 1.5 cm,

in diameter was punched through the center of the stamp in order to invalidate

the stamp in accordance with the provision of Article 64 of the Royal

Cedula of February 12, 1830. [32]

USE

OF ADHESIVE STAMPS ON PROVISIONAL STAMPED PAPER

As

already explained on pages ___, during the period from July 1. 1886 to

December 31, 1887, adhesive stamps, both postage and revenue,

were affixed to the current stamped

paper in order to compensate for the

difference between the price of the current stamped paper and the

price of the stamped paper required by the Royal Decree of May 16, 1886.

For example, adhesive stamps of the total valve of 12 pesos might

be affixed to a sheet a of ILUSTRES stamped paper, whose price was 8 pesos,

of the biennial period of 1886-67. The result was

a sheet of stamped paper of the first class (SELLO 1) valued

at 20 pesos, as required by the Royal Decree of May 16, 1886.

During

this same period adhesive stamps, either postage, telegraph or revenue,

were frequently affixed to a sheet of “common” paper in order to produce

provisional stamped paper of any required class and price. In this case

the total value of the adhesive stamps affixed was the price of the paper.

Figure L shows a specimen of provisional SELLO 3, the price of which was

250 mil de peso, produced by affixing one 250 mil TELEGRAFOS stamp to a

sheet of “common” paper. The manuscript cancel of “14 Mayo / de 1887” indicate

when this this provisional SELLO 3 document was executed.

Figure

12

ADHESIVE

STAMPS ON DOCUMENTS SUBJECT TO MORE THAN ONE STAMP TAX

The

use of adhesive stamps to produce provisional stamped paper should

not be confused with the affixing of adhesive stamps to documents written

on stamped paper in order to pay a stamp tax which was in addition to the

requirement that the document be written upon stamped paper. The

stamp law required that public officials should collect a fee for signing

certain documents. This fee was collected by affixing to such documents

adhesive DEREGBOS DE FIRMA stamps for the amount of the fee. But law might

also require that such documents be written upon stamped paper. In

this case the document would first be written upon stamped paper of the

class required by law. The adhesive DERECHOS DE FIRMA stamp would

then be affixed to the stamped paper in payment of the “signature fee”.

The

law required that deeds be written upon stamped paper, but if the deed

acknowledged the receipt of a sum of money, an adhesive RECIBOS Y CUENTAS

stamp must be affixed to the document after if had been written

upon the required stamped paper. Such a document indicated the payment

of two separate and distinct stamp taxes.

THE

“RESSELADO” SURCHARGE

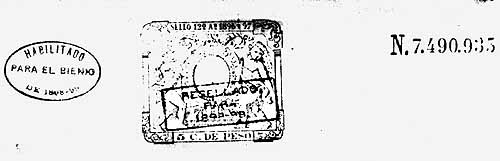

Figure

13 shows a specimen of stamped paper of the regular issue of 1896-97

which bears two surcharges. At the left of the stamp is an oval surcharge

which reads “Habilitado Para el Bienio De 1898- 99)” (Made Valid

for the Biennial Period of 1898-99). This surcharge undoubtedly was applied

by the Spanish Government prior to the occupation of Manila by the

American forces in August 1898. Across the face of the stamp is a

second surcharge, which reads “Resellado Para 1898-99”

(Restamped for 1898-99). This Resellado surcharge, which occurs in

several different forms and is also found on adhesive revenue stamps

and on postage stamps, has been the subject of considerable controversy

among collectors of Philippine postage stamps. It appears, however,

that at the time this controversy arose, the fact was unknown that the

“Resellado” surcharge existed on adhesive revenue stamps and on stamped

paper. If this fact had been known it might have altered the conclusions

of those who have claimed that the “Resellado” surcharge which occurs

on the Spanish-Philippine postage stamps of the issue of 1898 is a “fake”

surcharge.

Figure

13

The

revenue stamps and revenue stamped paper of the Philippines were not in

demand among collectors in 1898. Consequently there could have been

no incentive to produce a “fake” issue

of revenue stamps and stamped paper because there

was very little likelihood that such a “fake” issue could be sold to collectors.

Furthermore, if the alleged promoters of the so called “fake” issue of

postage stamps bearing the “Resellado” surcharge had applied the “Resellado”

surcharge to revenue stamps and stamped paper as a spurious means of giving

the appearance of authenticity to the “Resellado” issue of postage stamps,

full publicity would have been given by them to the “Resellado” surcharge

as it occurs on revenue stamps and stamped paper. Yet, the

existence of the “Resellado” surcharge on revenue stamps and stamped

paper seems to have been entirely unknown to those who engaged in

the controversy over the authenticity of the “Resellado” issue of postage

stamps.

The

story of the “resellado” issue of postage stamps told by Major F. L. Palmer

on page 53 of the “The Postal Issues of the Philippines” (J. M. Bartels

Co., 1912) is as follows”

| With

the arrival of American troops at Cavite on July 16, 1898, an American

Post Office was established temporarily on one of the ships in the Bay,

and on July 30 on shore at Cavite. From this date until the end of

the following year, a veritable philatelic chaos existed in the Philippines.

Mails were received and forwarded as opportunity offered, by all of the

numerous “governments” involved, each of which used the stamps which were

most available at the time. As a result there were numerous vagaries

in matters philatelic, and certain so-called philatelists contributed their

aid (though not without hope of reward) toward rendering confusion

worse confused. Thus we are compelled to consider not only the Spanish

issues but also those of the United States for the American forces, the

stamps issued by the Revolutionary Government, and certain “provisional”

issues for the Philippines and other islands formerly controlled from

Manila. Of the Spanish issues it is sufficient merely to add (to

what has already been noted) that they continued in use where available

until replaced by those of the government which later came to exercise

actual control. The issues of the Revolutionary Government will be

treated in a separate chapter, and those of the United States will

follow.

Of

the other issues referred to, the first to claim consideration, through

priority in date, is the fake “provisional issue” for Zamboanga, a city

in the island of Mindanao, which has been listed by Kehl and Galvez.

AS the true story of this issue seems never to been printed and is by no

means without its humorous side, it will be given in detail as related

to the writer by one of the two promoters thereof, who will be referred

to as Messrs. A and B.

A

and B, both well known philatelists of Manila, realized that Manila

must sooner or later surrender to the Americans, that Spanish

rule would pass away, and that philatelic changes must ensue. Wishing to

take time by the forelock, in order that any profits obtainable might not

pass them by, they conceived a shortage of stamps at Zamboanga, where Mr.

B had a personnel in the postmaster. Mr. A was a former Spanish

official who had friends in high places at Manila, as be procured

through them a decree providing for surcharging stamps for use at Zamboanga

on the plea of the alleged shortage. This decree is said to have been issued

on August 12, the day before the surrender of Manila; apparently the dies

had been prepared and the stamps obtained in advance, for the surcharging

was done that night by the promoters themselves. Later, and when opportunity

offered, these supplies (except those retained by A and B for their own

philatelic uses) were forwarded to Zamboanga where they were (more or less)

placed in use. In March of 1899, Mr. B was in Zamboanga on business

and his friend, the postmaster, then provided him with covers bearing these

issues, which the postmaster obligingly cancelled as of quite a range of

dates, presumably to avoid the monotony of one date only. Mr. B thoughtfully

placed a full set of this issue on a cover which he sent by registered

mail to himself at his Manila address and which was forwarded by the same

boat on which he returned. This letter was duly delivered to him in

Manila, without any other stamps or postal charge, through the American

post office, thus furnishing undeniable (?) proof of recognition

by the American postal authorities of the validity of this issue.

Upon

investigation by the writer himself at the post office, it was found that

this letter (identified by its serial number) had been received and delivered

without charge, though no memorandum existed as to what stamps it had borne.

In reply to questions the postmaster, who had also been an employee

in 1898-99, further said that in those early days and until the American

offices were established throughout the islands, the postal authorities

felt themselves compelled to receive and deliver, or forward, all mail

arriving at Manila without regard to what stamps were used from points

where American offices (and stamps) were not available to the senders.

He added that even letters bearing stamps the Revolutionary Government

had been so received and delivered. Such delivery or forwarding,

therefore, amounted merely to passing such matter through the mails without

postage and on account of the emergency rather than to any official recognition

of the validity of any stamps actually used. In further pursuance

of his investigation, the writer visited the Bureau of Archives where

search was made for the decree (or some record of it) authorizing this

issue; no trace of it could be found, but his does not disprove the

issuance of such a decree, a failure to which is readily explicable as

due to the carelessness of employees in a time of so great turmoil. |

|