PHILIPPINE

AIR SERVICE

1920 - 1921

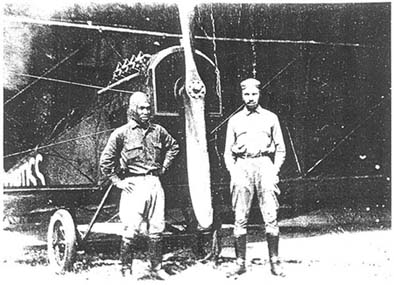

Air

Service pilots Calvo and Abolencia at the Camp Claudio

beach

runway along with their Curtiss Jenny.

From

the position of the military, aviation was a critical element for the defense

of the islands. As early as

January,

1915 the Commanding General of the Philippine Department in Manila cabled

the War Department with the following concerns:

It

is believed that adequate aeronautical personnel and material are essential

to the defense of

Corregidor

against artillery attack, especially from the direction of Mariveles. Artillery

from these positions could be capable of destroying the gun defenses on

Corregidor. On the other hand, if the location of such artillery is established

by proper (aerial) observation, the gun defenses of Corregidor are sufficiently

strong to destroy such hostile artillery.

Further

the Commanding General stated:

While

the destruction of the primary gun defense of Corregidor by hostile artillery

might not by itself cause the fall of the place, it would at least render

Manila Bay available to a hostile fleet.

In

less than 30 years. General Douglas MacArthur would be faced with the very

same concern — Corregidor being shelled from the mainland, with little

to no air support to provide reconnaissance or, more important, offensive

capabilities.

After

the end of the First World War, U.S. Army biplanes began to reappear in

the skies over the Philippines as the Philippine .Department began to re-establish

and build its Aero Squadrons.

At

the same time, surplus military aircraft, Curtiss JN-4D Jennys and Curtiss

HS-IL/HS-2L Seagulls (a name applied by the Philippine Air Service) provided

the first opportunity to train Filipinos to fly and to establish the first

commercial air service.

Much

of the credit for the promotion and creation of the Philippines' indigenous

air service belongs to Major Joseph E.H. Stevenot, a longtime resident

of the Philippines. He had joined the U.S. Army in 1914 at the outbreak

of the First World War, with the rank of captain. He received his flight

training at Brooks Field in Texas and qualified as an aviator. Although

he did not serve in Europe during the war, he returned to the Philippines

and became the commander of the Philippine National Guard's Aviation Unit.

Major

Stevenot was an aviation visionary who regarded the Far East as a widespread

territory well

suited

for aviation and the rewards it could provide a country and an entrepreneur.

An active member of the Aero Club of the Philippines, and a tireless advocate

of aviation in the Philippines, he lobbied for the cause and convinced

business and government leaders of the long-term value and importance of

aviation for the country's commerce and defense.

After

the war, Stevenot convinced his former flight instructor, Alfred J. Croft,

to come to the Philippines and join him in a venture to train pilots and

sell aircraft. Stevenot saw aviation as a growth industry in the Philippines

and throughout the Far East. Aviation would provide the long-sought-after

opportunity for the Philippines to be connected through regular commercial

transportation of people and goods, as well as to create a dependable air

mail service. In addition, an aviation service could play a key role in

mapping the islands, and in training the first generation of Filipino military

pilots, all key objectives of the Philippine Insular Government and the

Governor General. |